BETWEEN 1920 and 1935 the Seven and Five Society held 14 exhibitions in London. Of its 56 members during this period, 11 were women artists. At the 1926 exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery approximately half the exhibiting artists were women (10 out of 23) and it is in this year that the majority of women artists joined the group. These included Jessica Dismorr, Winifred Nicholson, Elizabeth Drury, Evie Hone and Lydia Pearson-Righetti. Betty Muntz and Sophie Fedorovitch, who had also exhibited in 1926, became members of the group the following year. Frances Hodgkins, whose name is frequently associated with the group, did not become a member until 1929 after the success of her solo exhibition at the St George Gallery. The first women members were Mary Attenborough (1922-3) and Lena Pillico (1923-27). In addition to these women, several women artists although not members also exhibited at the Seven and Five shows after 1926. (1)

It is in this period 1926-32, in what is regarded as the highpoint of the lyrical and neo-classical style which predominated in the group, that one finds the largest number of women artists participating. However, this fact does not form part of the accounts of this period in British art history. If the Seven and Five group is referred to at all, it is its dissolution in 1935 into the Seven and Five Abstract Group, and then Unit One, which has assumed a critical importance over this early period of the Seven and Five. By these means, the group is positioned as significant only in relation to the emergence of an important Modernist avant-garde, centred around Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore.

This picture of the Seven and Five as minor and of passing interest only is underlined by characterisations of the 1920s and early 1930s as ‘curiously rootless’ and a ‘hiatus’ in British art history. (2) Timidity, provincialism, and conservatism are the most frequent adjectives applied to this period where Modernist initiatives and Great British artists (male) are sought after, but not found. Apart from the war paintings or the continued careers of artists established before the First World War (all male with the exception of Vanessa Bell), it is not until the emergence of Unit One in 1935 that the condemnation of much work in Britain as provincial, backward or slavish imitations of art produced in France stops. The historical treatment of the Seven and Five is symptomatic of this approach.

On the one hand, it is as though the art of this period has been rendered effete/’feminised’ and roundly condemned by the absence of a distinguishably avant-garde group of virile young male painters, while, on the other, it deliberately ignores the work of the women artists of this period as a whole but renders as exceptional the occasional woman artist. Vanessa Bell, Barbara Hepworth, Frances Hodgkins, and, since their exhibitions at the Tate in recent years, Paule Vezelay, and Winifred Nicholson would all fit into the category of ‘great exceptions’, but this account is structured by the absence of women artists, en masse.

The Seven and Five was regarded as an alternative exhibiting space from the London Group and its domination by Bloomsbury for contemporary artists interested in modern art. Its members had frequently exhibited in either the London Group itself, or the New English Art Club and, in the case of some of the women artists, the Society of Women Artists. The Seven and Five artists chose also to turn photo into painting either independently or collectively at contemporary modern art galleries like Lefevre, the Leicester, Beaux Arts, Goupil, or the St George Gallery. Charles Harrison states that the major achievements of the Seven and Five consisted in the development of a Modernist sensibility in British art and the absorption of many contemporary ideas in French painting particularly from the work of Jules Pascin, Dunoyer de Segonzac, Marie Laurencin, and Kisling. (2) His views reiterate Clive Bell’s conviction of 1920 that the best English painters were equivalent at best to France’s most second-rate. Thus Harrison sums up their still lifes and landscapes as more ‘appropriate for the expression of individual sensibility than for changing the currents of contemporary thought’ (the latter, presumably his ideal role for the avant-garde!). Again a very negative picture of the group is constructed, aided by Bloomsbury’s prejudices against English art in favour of France, at the same moment in which Bloomsbury dominated the English art scene.

By contrast, H.S. Ede wrote of the Seven and Five: ‘Fleeting is the watchword and in this watchword there is a straying wandering delight. Painting is not now for eternity, it is the expression of the moment, and the moment will bring its own new expression. Perhaps it is really an approach to the musical idea. (3)

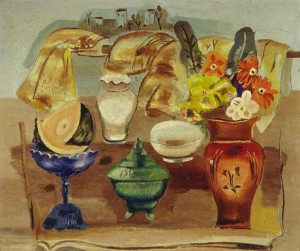

Like Helen Sutherland, who also collected these artists’ work, it was the combination of poetry/lyricism, music/rhythmic and flowing forms, and modern art, either approaching abstraction or carrying a fresh/naive or child-like vision of the world, which appealed to Ede. Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, became its created environment. Still life, landscape, and portraits of family and close friends were the preferred subject-matter of many of these painters. The women artists were no exception. The works (small oil paintings and water-colours) were often painted in pastel or acid colours with deliberately na’ive and spontaneous free-flowing forms. Again could the reason for their dismissive treatment be because all of the above qualities carry with them the strikingly negative associations of the amateur or feminine painter?

Ede’s phrase ‘beauty caught on the wing’ was applied directly to both Winifred Nicholson’s and Frances Hodgkin’s work. Their spontaneous and direct method of working on canvas or paper laid flat in front of them and completed in only one sitting, created that ‘expression of the moment’. In many of their still lifes, flowers on a shelf or the comer of a window sill in the foreground contrast with the horizontal planes of landscape rising behind. It is a form of composition distinctively their own.

Because of their colour, form, and subject-matter, both these artists’ work (and Hodgkins’ in particular) was recognised as ‘essentially feminine and having a peasant or folk-art quality’. (4) Again what they achieved has become the grounds for their dismissal. However, much of the work by their contemporaries, like Cedric Morris and David Jones, shared these qualities. Many works produced in the 1920s and 1930s were small in scale either due to a shortage of materials in the immediate post-war period, or a generally depressed art market and shortage of public commissions, and the resultant relative poverty of artists. New developments in paint manufacture, including new ranges of pre-mixed colours, contributed also to these artists’ choice of palette, moving from a more primary-based Post-Impressionism towards the acid greens, violets, purples, and tangerines which characterise it. Thus one can find other reasons for the qualities present in these works without resorting to an essential femininity as an ‘explanation’, nor can these qualities be seen as gender specific, though a good case can be put forward concerning Frances Hodgkins’ originality and influence in creating such forms.

In the light of Winifred Nicholson’s show at the Tate, it is interesting to examine her work within the context of the Seven and Five. This was absent from the Tate’s presentation of her life and work, as they chose to emphasise instead her individual and subjective approach to painting through her theory of colour and her relationship with Ben Nicholson. Thus we are presented with an interesting, individualistic, but very ‘minor’ woman painter, but once married to, and still good friends with a ‘major’ male painter. Winifred Nicholson’s status as minor, provincial, and second-rate, as with other members of the group like Cedric Morris and Frances Hodgkins, is reinforced by this emphasis where the qualities of the work are seen as the result of individual preferences and failings, and not as a quality constructed or sought after by the artists and their contemporaries. It is in this way, however, that her distance from the international successes of her husband’s abstract modernism can be retrospectively secured. For, in spite of acknowledging the influence of both his wives upon his development as an artist, Ben Nicholson writing to the art historian, Mary Chamot, in 1935 was careful to maintain this distance. He carefully distinguished himself from his first wife by associating her work with that of the early Seven and Five, and his own with the classical abstraction for which he later became known. This division is structured by gender. Nicholson wrote: ‘It would be misleading to bracket our names because the work we were doing at that time was extraordinarily different, the difference between very bright flower paintings (feminine) and very sober brown and grey still lifes (masculine)–also I do not at all associate my work at any period with Ede’s idea of ‘beauty caught on the wing’–indeed quite the contrary as I have always had in my mind something particularly sustained and enduring’. (5)

The break-up of the Nicholson’s marriage and Ben Nicholson’s subsequent re-marriage to Barbara Hepworth, was a key factor in the dissolution of the Seven and Five into Unit One. Individually, both Ben and Winifred Nicholson, after their separation, began moving towards abstraction. Winifred Nicholson deliberately became less involved in the organisation of the Seven and Five after 1931, although she continued to exhibit (under her mother’s family name, Dacre), sending work from her new home in Paris. Ben Nicholson’s dogmatic promotion of abstraction, coupled with the election into the group of John Skeaping, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, precipitated the resignation of a large number of its former members bet-wen 1931-4. Those who resigned included Jessica Dismorr, Evie Hone, Edward Wolfe, Maurice Lambert, David Jones, Sophie Fedorovitch, Lydia Pearson-Righetti, P.H. Jowett (formerly the Secretary), Edward Bawden, and .

The work of many women in the Seven and Five, with the exception of Winifred Nicholson, Frances Hodgkins, and Barbara Hepworth remains practically unknown and is rarely, if ever, shown. Though much basic empirical work about these women remains to be done, the early period of the Seven and Five, because of the large numbers of women as both members and exhibitors, should be of particular interest to feminist art historians for two reasons. Firstly, because of the way existing accounts of the group have been constructed to exclude women artists, and secondly, by opening up this whole area, issues of gender bias in art history and questions concerning difference are brought to the fore.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.