I like German painter Daniel Richter’s work. I’m not often compelled by contemporary, figurative painting, which is a shame because I am a figurative painter. Despite what many think, and because of what many people think, painting is a difficult medium. I first saw Richter’s work in a 2003 issue of Modern Painters. I read the article twice and looked at the paintings for months thinking about my own relationship to the medium.

My own work explores psycho-socio-sexual themes through figuration. Damaged but hopeful, I like the term “Optimistic Dysfunction” to describe them.

Daniel Richter’s paintings are powerfully charged with social and political content. They reveal a genuine interest in humanity as a collective, but through a dark, dark lens. Ergo, it seemed logical to me, to call him an ‘Optimistic Dystopian’.

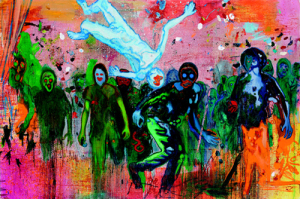

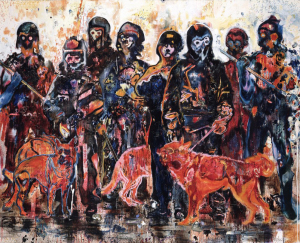

Richter’s paintings are huge, high-voltage, almost formally over-stimulated, sometimes absolutely beautiful and sometimes not. They are confusing in a good way, sometimes loud, sometimes soft, always appearing to say something provocative. Richter’s painting vocabulary, his palette, his imagery, seem wildly self-permissive yet canny, and are at turns humorous, threatening, sexual, tender, raw and lyrical.

This spring the Power Plant brought Richter’s work to Toronto, a show that will move onto two other Canadian venues: The National Gallery and the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at UBC. There are also lots of people like large modern canvas art. The conversation that follows roams over a fairly wide and often digressive terrain that to me provides a good introduction to the overall meaning of Richter’s work.

ELIZA GRIFFITHS: I haven’t seen this mentioned in discussions of your art, but does music have any direct relationship to your work?

DANIEL RICHTER: Well it does to me as a private person but I don’t think that my work is readable in the sense that you have to know certain music to understand it. But sure, if you want to think about it in an analogical way, if you relate compositional problems to structural problems … You like Schoenberg but you want to have the impact of, say, late Throbbing Gristle. Some stuff is like a one hit wonder, others just need a lot of space and I try to integrate all that. I don’t think you need any knowledge about what I’m listening to in order to understand my work. So it’s more a private question. As a private person I would say yeah, my work is based on that–the more music you know and understand the more you understand the world

EG: I meant it more in terms of the effect you might be after. The sensation your paintings produce reminds me of rock n’ roll/punk spectacle.

DR: I don’t know about that … but, if you say that, I enjoy it. For sure it structures your brain and your thoughts, like it’s different when you’re listening to Leonard Cohen, for example. Your brain structure is different than when you listen to Black Flag and Beethoven. Maybe I could say it like this. For sure my paintings work on a level that has an impact that is similar to subcultural pop music, but on the other hand it’s very strongly related to compositional and historical problems and so on.

EG: There are a lot of crowd scenes in your paintings and they convey to me the impact of noise and the adrenal, sexual, aggressive potency of the crowd. I don’t see a lot of paintings that have that effect.

DR: I do a certain number of paintings based on the stage as a historical setting: Rock, theatre, cabaret, zoo or whatever. But … it’s images not sound, and music follows different rules. I try to do paintings as paintings as far as I can. Sure I try to stretch that and it’s a goal to try to do something that is historically based and work it in a modern way too. It’s personal too. I would like to do paintings that I would like to see myself, and what I like to see depends on what I learn to think. I’m as much art individualist as a painter as I am a collective individual like everybody else.

EG: There is a very dense amount of information in your work, on a visual level both pictorially and formally, as well as on a less direct conceptual front….

DR: There is a lot of information coming into the brain and the more you try to organize this information the more precise certain points get, but the more confusing the whole structure gets. But that is somehow what my work is about, I try to refer to both points and not only these two points but the contradiction that is in between.

EG: What determines your choice of imagery?

DR: I follow my own five-year plan, like the Soviet Union.

EG: Really?

DR: I did five years of abstract painting. I decided now I have one more year of this kind of work and then I’ll see. I’m already working on other ideas, but I’m not sure, I don’t want to force it. To every position there is a counter-position, a dialectical way, so when I did abstract painting I really believed this kind of stuff was inheriting some kind of truth about thinking of the world in images. I so much denied figurative painting that I ended up a figurative painter.

EG: Why deny figurative painting? Did you think it was literal or boring?

DR: Yeah. I didn’t like the way it’s organized, it seems to be always the same, and then I ended up the total opposite. My art ended up like a typical male, something that doesn’t exist anymore, that was the interesting anachronistic fact. A lot of people blame me, especially say, from a kind of progressive attitude, say ‘oh, that this is work that is so male, so white’.

EG: Has this come from feminist positions or where?

DR: No, that is giving a bad name to feminism. I always say, look at the work, judge it as a work. It’s about insecurity, and it’s about how to deal with topics. For sure I want people to look at it, that’s why I choose to do it big. I don’t want to do like subtle, small stuff that is like a little painting or a little drawing.

EG: While I do see vulnerability in some of your work some of the paintings come on like a bomb, pushing out into the space a very dominant masculine, sexually predatory, aggressive energy.

DR: They don’t want to be ignored … but I was always very aware of that and I know that people look at it as a male thing. I think the iconology works like that. I say, ‘well, listen, there are no men that have orange eyes and there is nobody looking like that,’ it’s a painting and that is why I choose to do it like that. If you want to identify with it and say it’s women, I wouldn’t say no…. I know it’s tricky and there are very few of my paintings where there are women definitely as women and it’s really hard to do if you don’t want to work in a low, provocative, or gender victimizing thing…. I get upset when people blame me on this and say it’s like this ‘white heterosexual stuff’. Don’t give shit to me, take a brush and make paintings. Don’t limit yourself and think that a sensitive person has to do something with felt pen and a poetic piece of paper for the rest of their life. Subtlety, aggressiveness, subjectivity, these are all cliches; you can use whatever you want. If you think you can do an intelligent work about gender with five kilos of painting, try it, maybe you will fail. Art is not about playing the safe side.

EG: But contemporary figurative painting can be more loaded than some other forms in terms of interpretation vs. intention …

DR: Yeah, I know. This is another reason why I choose to worry often. There was really an open space and I said yeah, I don’t want to do this black/white/male/female thing, I want to do the ghosts of people. The thing is, when you represent your own gender and class, you can be as much blamed as … The biggest piss-off is when young, white, middle-class liberals paint like, black rap problems. This is really double-exploitation. I mean, if you have any respect for that thing, keep away from Chuck D. Like all these sons of doctors who play in crossover bands, I think like, ‘Jesus man, play folk guitar’.

EG: I have a question about one of your paintings that I’ve only seen in reproduction. It’s an image of two men beating a horse with sticks. It’s a really distressing image, but you’ve said some really interesting things about it and I’d like to hear a little more …

DR: It’s a speculation on the decision of what is right and what is wrong, and this does not lie in the painting, it lies in the ideological decision. If I say, “the horse was a bad horse. The horse was an old Nazi, beat it to death’ … it’s humanistically a bad thing, but we have to do it,’ which is actually what governments are doing now. It’s like you see images that are bad and say, ‘yeah, it’s a dirty job, but it has to be done.’ There may be truth in that, there may not be truth in that.

EG: Are you talking about mass media and propaganda?

DR: Yeah, I’m talking propaganda … For example, when you look at the images of Lindy England, the woman who is now the most known soldier in the Western world, you have something that even has an emancipatory effect, which sounds cynical, but you see that given a uniform, and given the possibility to torture men, women are equal to men. But the interesting thing about it is, aside from the moralistic impact that we should condemn this woman and the other soldiers is that … on a certain level it’s a capitalistic feministic win, it shows a victory. It shows women can do what men can do. The Western woman is able to be as bad or as good as men. It just shows progress and that there is no progress in terms of identity and speculation about sexuality. The impacts of these photos is a disaster, I think they should be court-martialed and put to death. Another thing that it shows is that the American soldiers are totally sexualized, because classically you torture somebody, you cut off their ear, but now it’s like really enjoying the part of being the person who is degrading the other, it’s like doing your own pornography. That’s a really different thing than classical torture, like what these pathetic guys from Al Qaeda did, five idiots with masks somewhere in a cave, they don’t have any power, they just represent a small number of people. Related to the other (U.S) image, it’s a weak image. The woman, having a naked man on a leash, that’s a strong image.

EG: I find a strong sense of that sort of violence and sexuality implied in your work. Having said that, you are concerned about the responses people have to your work, do you censor yourself when you are creating your imagery?

DR: No, but when I’m in the studio for sure I think of the reactions. That’s why I go to openings even if they are stressful. It’s the only time in the year when I see and have all the eyes of the people and they complete my way of seeing. I can see them looking at the painting and then I can see if I failed with the painting or didn’t.

EG: A lot of people have discussed your work in terms of history painting and yon seem to have a deep interest and knowledge of current events and German and Soviet history, particularly the human dimension …

DR: I believe that understanding history means understanding mankind. I’m not so much interested in ideological or moralistic views I’m interested in what happens, why, when, and how it is to be judged. Like, why did this whole century, which had all the possibilities to fulfill a utopia, end in a total disaster? And how did the emancipatory movements, which were the communist, social democratic, and whatever, the feminist movement, why did they fail? What happened to these utopias and why did they go wrong? Nowadays we are in a situation where we can just be unideological because we have no responsibility … it’s just sad.

EG: There is no vision now?

DR: There is not only no vision, there’s no counterpart. Like you could defend the Soviet Union, but you were lying too, because the Soviet Union was not a paradise, it was a horror. And now you have a very different version, of, I wouldn’t say a horror, a kind of agony that is spreading all over the world. Because the Western world is not living in fear and pain, it’s living in agony and boredom.

EG: I’ve noticed an emphasis on collective identity and social groupings rather than the individual in your painting …

DR: That came to me analytically, because when you look at the history of modern painting, after the Second World War, the so-called masses don’t play any role, which is very astonishing. I was just wondering why nobody tried to represent that anymore. I wonder about nowadays, like during the 90s, when it was not definitely necessary to be politically active, a lot of people in the art world were politically active, and now when I look at work I think, it’s so intimate, so private, campy or funny. I just wonder why everybody talks about the drama of this new confrontation with an anachronistic enemy on the one hand, and a democracy that it would like to defend but which makes you uneasy to defend, and nobody deals with it. People do like, painting of pop stars. I wonder why nobody tries to reflect on that. Everything is so private and not generalizing, opportunistic in some ways. We defend our little happiness … and for sure we have a right to do that, but I always thought art is about something.

EG: It’s a challenge to make work about that material that isn’t didactic. Do you believe that painting has the capacity to be a form of activism?

DR: No. In a society that is very homogenous and authoritative, a poem about a flower can be revolutionary. Other way round, in a society that is tolerant and liberal, making a big revolutionary bahoo without any activism doesn’t make any … other than ending up on a collector’s wall. A painting is for some kind of contemplation. I mean that seriously, I don’t mean like sneaking out of the world, but contemplation in the sense of thinking about who you are, and what painting offers you in relation to the world where you are existing. If you want to change the world go and kick somebody’s ass, go to a demonstration.

EG: By creating paintings that are thought provoking, by deliberately using groupings of chairs in the middle of your painting installation as you have, you invite a measure of social discourse. Isn’t that some measure of activism?

DR: For sure I want people to see it and I want people to sit there, but I know what I’m doing is painting. All of these paintings, if I’m lucky, are going to end up on the walls of someone who I’m totally opposed to politically. You shouldn’t lie about that. It’s a very simple paradox and the modern world of capitalism offers that.

Griffiths, Eliza

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.