THE LITTLE BOOKS, for which Beatrix Potter is best known, form just a part of a life in which she tried to achieve personal independence and fulfilment while at the same time remaining a dutiful daughter in a middle-class Victorian family. Her wealthy and privileged background was a mixed blessing. On the positive side was a South Kensington home, in which books and painting materials were plentiful; long summers in Scotland or the Lake District which stimulated and nurtured Beatrix’s interest in the natural world; and parents who themselves painted and collected art, and took Beatrix to exhibitions from an early age.

Beatrix’s childhood was sheltered and solitary because her parents discouraged close friendships. Besides Bertram, her younger brother, Beatrix’s companions were the many pets they kept in the nursery. These they observed, measured and meticulously drew, activities which furnished Beatrix with an extensive knowledge of animal anatomy, behaviour and characteristics for the stories and illustrations of the Little Books.

While Bertram was sent away to school and university, Beatrix was kept on a short rein, privately educated and expected to become involved with running the house and paying social visits with her mother. This insular existence led Beatrix, at the age of 24, to attempt some degree of economic independence by selling Christmas card designs.

Beatrix Potter seems to have been a strong-willed woman, unfettered by prevailing ideas of what was fitting for women to do. In the 1890s she made over 300 drawings of fungi and wrote a paper on experiments with the germination of spores. This shocked the exclusively male scientific establishment and was read to the Linnean Society by a man because women were barred from meetings. It is a sign of her determined temperament that when Peter Rabbit was rejected by six publishers in 1900, including Frederick Warne who wanted her to change the format which she refused to do, Beatrix published it herself in an edition of 250. Warne published the commercial edition in 1902.

The money which Beatrix Potter earned from the sale of the Peter Rabbit books she used to buy land in the Lake District, her first purchase being one field in Sawrey, in southern Lakeland, in 1903. That marked the beginning of her life as a Lake District landowner and conservationist. The Little Books and the merchandise that went with them, the first examples of which Beatrix Potter herself designed, were a means of financing her passion for preserving traditional Lakeland farms and farming methods and the Herdwick sheep which she started breeding and showing in the 1920s. At her death, Beatrix Potter owned over 4,000 acres of land in the southern Lake District which she gave to the National Trust. Many stories are set in the Lake District. In 1905 Beatrix Potter bought Hill Top, a working farm in Sawrey, in which the Roly Poly Pudding is set.

The constant input of realism in Beatrix Potter’s illustrations, of particular places, particular animals and people, give them an air of actuality rather than fantasy. Her stories often grew, as did The Tale of Peter Rabbit, out of tales she made up in picture letters to children. Some of the stories are very simple, like The Tale of Mrs Tittlemouse, while others are longer, more complex dramas involving conflict and fear like The Tale of Mr Tod. The books are not ‘peopled’ only with sweet, ineffectual, cuddly animals but abound with diverse creatures of varying habits and purpose. It is disappointing, though, that Tom Kitten goes off and has an adventure while his well-behaved sisters Moppet and Mittens stay at home.

Elements of people she knew also went into Beatrix Potter’s animal characters. Mrs Tiggywinkle was partly based on an old Scottish washerwoman, Kitty McDonald, who Beatrix described as ‘a comical, round little woman, as brown as a berry, who wore a multitude of petticoats and a white mutch’. Her use of animal protagonists has many precedents, among them the fables of Aesop which Beatrix sometimes adapted for her own use. She never felt able to draw people with the same fluid ease and skill she brought to her animal images.

After 1913 Beatrix Potter published less: her eyesight was no longer good enough to work on such a miniature scale and she was more interested in enjoying her farming. She never courted the publicity which so easily could have been hers and went to great lengths to preserve her private space. The journal she wrote from her teens was in code which remained unbroken for 80 years, and while living at Castle Cottage, Sawrey with her husband from 1913, she kept up the pretence of living still at Hill Top farm in an attempt to sustain the relative solitude she was accustomed to since childhood.

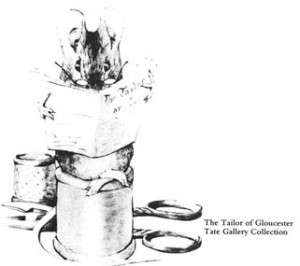

Beatrix Potter wrote and illustrated 22 Little Books, just right for a child’s hands, which have given pleasure to children and adults alike. They are written with economy and clarity in a deceptively simple style, illustrated with glowing watercolour scenes and spiky, concise pen and ink drawings. Her miniature paintings, full of naturalistic detail, place her in an English tradition of illustrators including Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott who Beatrix particularly admired. Waldemar Januszczak, writing for the Guardian, shows his contempt for art made primarily for children as the audience, when he describes the Tate exhibition as ‘perfectly ridiculous’. His comparison of Beatrix Potter’s work with Postman Pat and Noddy books, the illustrations of which have a toyland, two dimensional quality, shows him equating two radically different approaches to illustration. It is as if he has never actually looked at Potter’s work, dismissing it as small, illustrative, feminine in its appeal for young children and therefore insignificant. The images in the Little Books are part of a larger oeuvre of rich, sensitive watercolours inspired by a love of and interest in the natural world.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.